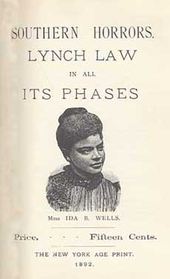

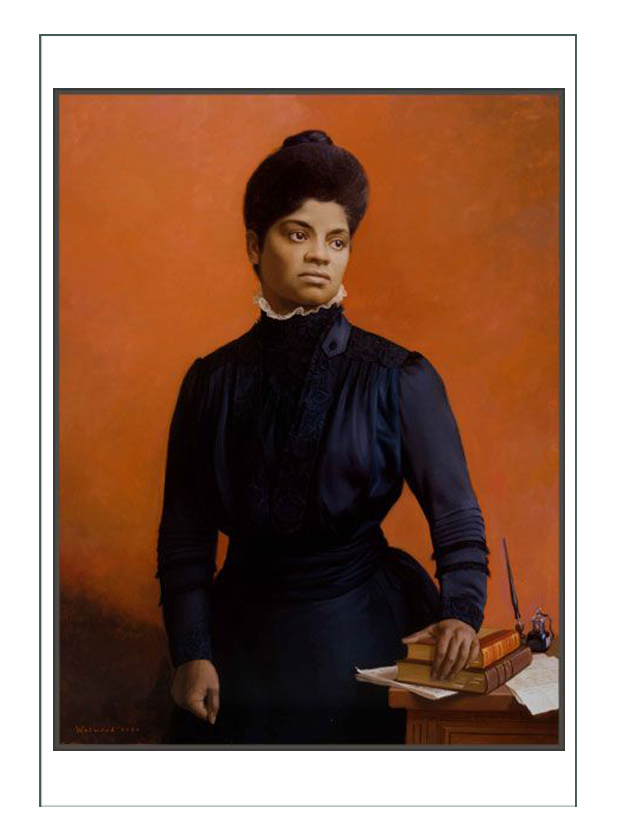

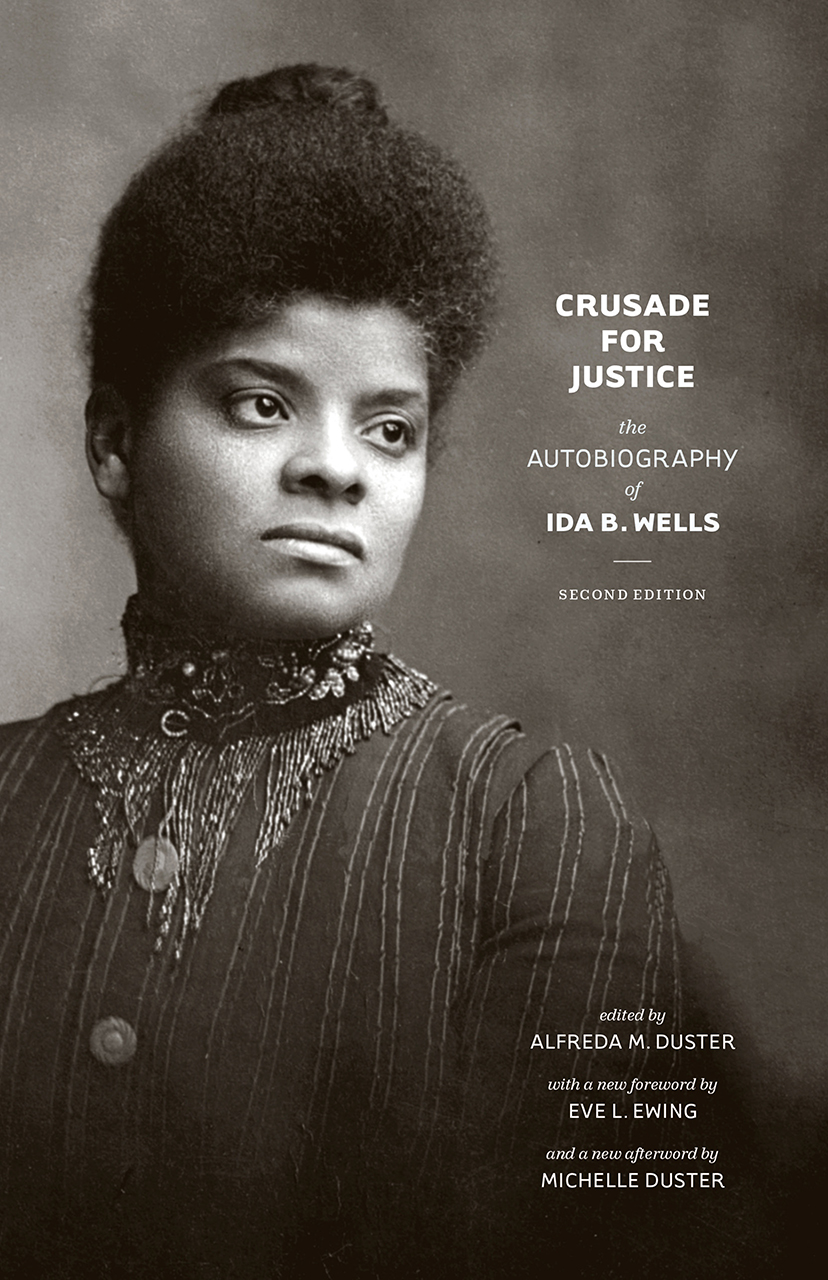

Ida Bell Wells-Barnett

(July 16, 1862 – March 25, 1931)

School segregation

In 1900, Wells was outraged when the Chicago Tribune published a series of articles suggesting adoption of a system of racial segregation in public schools.Given her experience as a school teacher in segregated systems in the South, she wrote to the publisher on the failures of segregated school systems and the successes of integrated public schools.

She then went to his office and lobbied him. Unsatisfied, she enlisted the social reformer Jane Addams in her cause.

Wells and the pressure group she put together with Addams are credited with stopping the adoption of an officially segregated school system.[51][52]